FWM: You are an international artist and author who works from your home studio on Oregon’s shore of The Columbia River. Share your background.

I have a BA in Fine Arts and Arts Administration an MA and Doctorate in Human Development and Organizational Systems which researches the nonverbal interactions used in drawing. But it was my three-year certificate in Fine Arts from the Mendocino Art Center in California where I feel my art education really started.

For four decades I’ve juggled earning a living from making and selling art, freelance writing and teaching. I have a pretty disciplined schedule: write first thing in the morning, then exercise, followed by eating a high protein meal then it’s on to the business side of art and writing, promoting. Late afternoon is studio time.

I have just built a new home and studio on The Columbia River in Oregon where I am preparing to enter a more commercial side of marketing my art.

FWM: Your paintings have captured the emotion of the moment. Share your works.

I am a visceral painter. If I don’t feel it, I don’t paint it. This is why I mainly stick to landscape painting where I become a conduit channeling the underlying spirit of the land. I work on location, mostly alla prima, and never use photographs. When I worked as an art professor inn Kuwait, I was not inspired by the landscape, plus it was too hot and too dangerous for a woman to go in the desert alone and paint. So, I turned to pomegranates. For six years that is all I painted. In this fruit I found the spirited crevasses and planes I find in geological formations.

FWM: You believe teaching art is an art itself. Explain.

Teaching to me is also an art form. I have to adapt lessons based on the age, ability or culture in which I’m teaching. Combining senses with subject knowledge I craft a line of inquiry that relates to a particular student or student body. More than knowledge-based outcomes, such as test scores, I value the process of learning and how it manifests into self-reflection, further inquiry and exploration of a topic or skill. I teach art to kids with different physical and developmental abilities and delight in their personal and professional growth.

FWM: Tell us about your new book, Babe in the Woods: Self Portrait

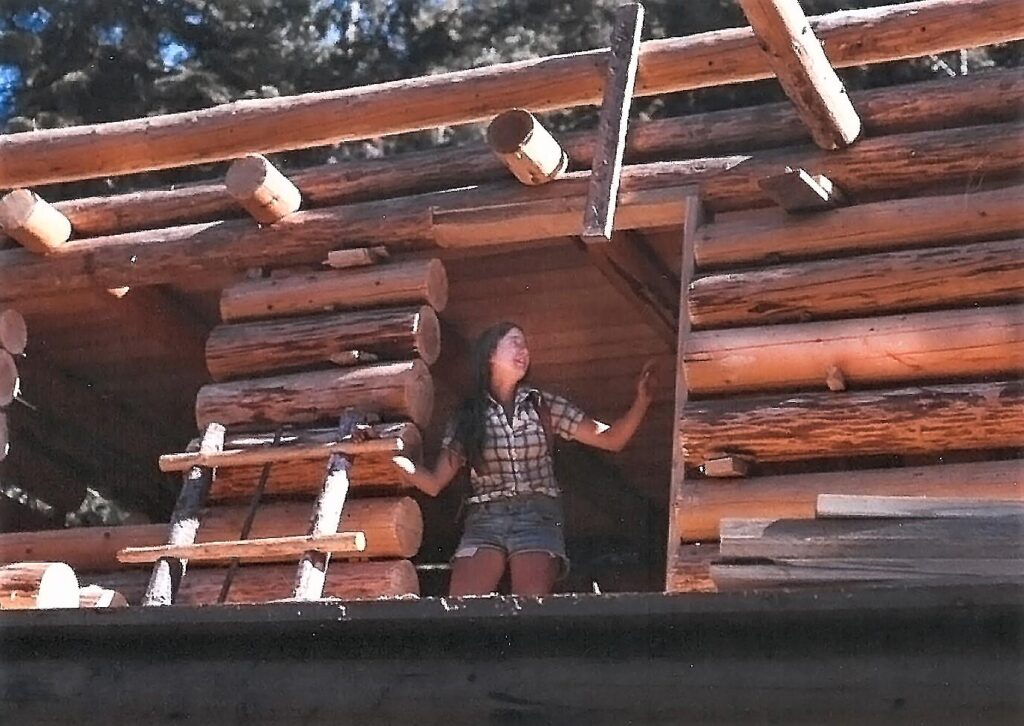

Self Portrait, is the second in the Babe in the Woods series. My first book, Babe in the Woods: Building a Life One Log at a Time shows the origins of a girl who had an idea the night she was orphaned. It evolves with the manifestation of this idea: build a log cabin in the wilderness. In the process we see an 18-year-old girl learning to use tools forged for men and working in what, back then, was seen as traditionally male work. It is also a story about adapting and overcoming internal and external challenges, healing through bone breaking work and learning to trust in strangers and to trust in personal independence.

Book two, Self Portrait is more about this girl getting a grip on learning to live more comfortably in the wilderness while building a second log structure as a post log cabin building test. Could I build this one all alone? This goal was greatly reshaped by having to deal with rouge bears. Then there is the isolation of living alone, developing as an artist and having time to reflect on a sorry past that led me to the mountain.

FWM: What is it about being in a log cabin that fuels your creativity?

It is the simplicity and isolation that strips me to the core. Living without any electrical or telephonic devices or people around, I have to listen to and to trust in myself without any distractions or external support. This allows for intuitive channels to reopen and reshape my observational skills.

At the cabin, I still live the same way I have since I was 18 years old. Using the same tools, chainsaw, axe and maul, to get heat and the same two buckets to get water and kerosene lamps for light. There is no phone reception and the closest town is 13 miles down a rutty road. As I get older, I have to consciously remind myself how easy it is to get hurt. I no longer do things I used to take for granted like chain sawing down big trees.

I alternate cabin life with living in a new home and studio with all the conveniences; I even own a robot vacuum. At least twice a month I drive 200 miles, one-way, to work in the forest or on the cabin where I reclaim what I lost in the lap of luxury. I clean with rags and straw brooms made by the blind.

FWM: What it really means to live with no electricity, phone, computer or running water?

Imagine if you want a glass of water or want to wash clothes or take a bath and there are no faucets to supply water. Imagine wanting to call a friend to complain you have no water and there is no phone service. Imagine wanting to email, shop online, Google a fact and you only have a pen and paper. Imagine your electricity is out and it is dark by 5pm. How are you going to entertain yourself? I read, write and draw by the light of a fireplace and kerosene lamps.

When I am at the cabin, I scoop buckets of water from the creek and haul them up hill, upstairs and into the cabin where I fill vessels. My hot bath is derived from sinking a hose in the creek, filling a 55-gallon drum with water, heating it in another barrel below from a fire built with wood I’ve sawed and split. With no phone I have only myself to talk to, sometimes a bear lumbering down the path, a goshawk or my little terrier dogs.

FWM: Your book has garnered much attention of tv and radio interviews across the country. What is it about this story that is resonating with the audience?

I think because it is told simply and directly about how one young woman achieves a goal by learning to use tools to find the skills required to rebuild a home she lost and, in the process, finds herself and friendships in a small town

FWM: What are the benefits of living without technical distractions; one can concentrate on listening to and learning from the land?

One summer I returned to the cabin after working another academic year as an art professor where I was tethered to a computer and telephone. I was standing on the porch when my cell phone rang and I immediately went to retrieve it from my back pocket. Then I realized I was responding to a bird trilling. It was a Pavlovian response that made me realize how conditioned I was to react to what sounded like a ring tone. There is no phone or cell reception at the cabin.

Without the distractions of a phone or computer or even a radio my mind begins to calm down. The physical demands of just keeping warm, watered and fed, rewire nerves adapted to tapping on electronic devices. Over the course of a couple of days, a holistic change takes place over body and brain. When I return to electrified life, I appreciate but do not abuse the privileges of immediate light, heat, and water.

FWM: Babe in the Woods: Self Portrait is the second in a three-book series. Can you share a glimpse?

From the first page

Bears had never bothered me before I shot one that summer on the mountain. As a borderline vegetarian, I reasoned, since I deliberately killed an animal, I had to eat a bit of animal deliberately killed. Not entirely to restore karmic equilibrium, but so I could chew upon the carnal rush of slaughter.

On that summer day, when hummingbirds drilled air hot enough to bake vanilla smells out of ponderosa pine, I waited, primed to kill, on my log cabin porch. When a black bear parted brush and stopped midway in crossing the creek, I grasped a thirty-thirty resting by my thigh. Leveled it on a two-by-four nailed across the railing, aimed, fired. The bear’s eyes blew open in shock before it faltered, staggered upright and bolted in a tilted gait upwind of a bullet so immediately embraced.

Days after the bear had been found dead, I felt the need to eat meat to restore the cosmic balance knocked off kilter—a mere trigger squeeze is all it took. It had to be wild. Killed in the wild and not from the bear I shot. I bummed a frozen elk steak from a runty hunter.

After it thawed I roasted the meat on a green willow stick over a twiggy fire beside the flashing creek, within spitting distance of where, only days before, I’d blown out a black bear’s rib bone with a borrowed rifle at three hundred feet.

I seared venison until it was as brown as the branch piercing it. Until flames licked away and nearly blackened what cardinal red was left of an animal that like the bear had browsed, a season before, upon pale, green shivery shoots. When it cooled, I bit into that charred chunk and chewed.

The creek continued to flow. The forest practiced its natural order; every leaf, twig, pine needle, rock and pine cone in forested rapport. But the animal in me got all riled up and I choked up before I could swallow: swallow the fear that had taken us both down.

Please share your social media handles.

Facebook: Yvonne Wakefield

Babe in the Woods Building a Life One Log at a Time

Yvonne’s Studio

Instagram: Yvonne.pepinwakefield

Linkedin: Yvonne Pepin-Wakefield